Why Hybrid & Concurrent Athletes Need Power & Speed Training

If you’re looking to combine strength and endurance training, there’s a few programming keys you need to get right to be succesful.

One of which is the inclusion of power & speed training; and by extension programming these correctly.

So, this article will explain why this is and what you need to know about adding power & speed training to your program.

Power versus strength: what’s the difference?

Strength refers to how much total force your body can produce.

Power refers to how quickly you can produce this force.

For example, a 1 repetition maximum squat demonstrates strength, while a vertical jump demonstrates power.

The primary difference here is the speed of movement. In heavy squats, you’re likely not standing up very quickly because the load is heavy. Conversely, in a jump, you are “standing up” as fast as you possibly can.

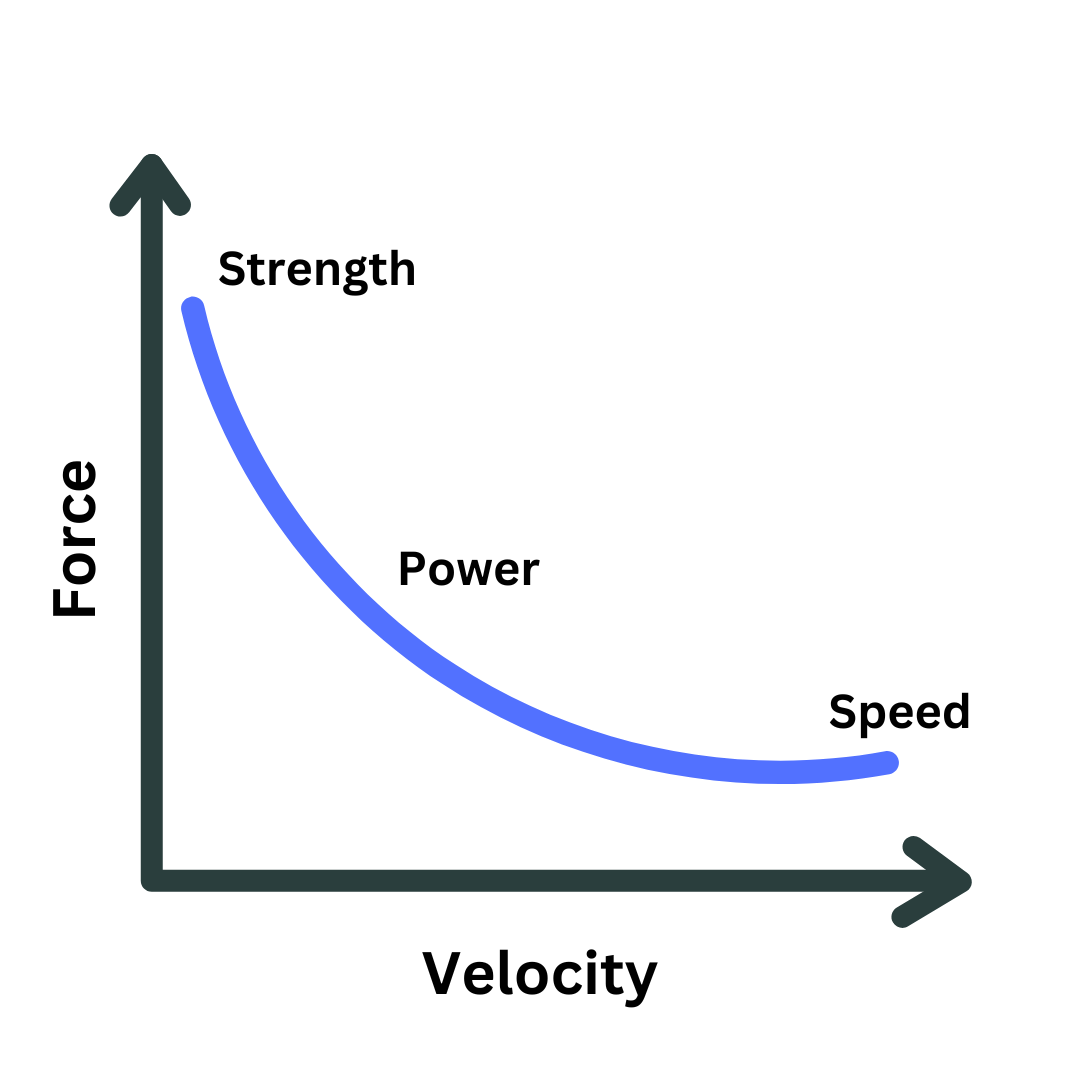

To be more technical, to train speed and power is to move to the right on the force velocity curve:

Understanding this relationship is important when drawing up training programs; and understanding what you are training.

Basically, the more weight you put on a barbell, the slower you will lift it up.

The less weight you put on a barbell, the faster you are able to lift it up.

In essence, the idea is to be conscious of if you are training strength (heavy weight, slow velocity), power (moderate weight, moderate velocity) or speed (low weight, high velocity).

Do note that the terms heavy, moderate, slow, etc. are all relative here. For instance, a classic example of training power is to train the olympic lifts. In these exercises, speed of movement is faster than heavy squats but slower than vertical jumps.

Nevertheless, how you go about training and improving each one of these will look different.

Why is this important for hybrid athletes?

By definition, any hybrid or concurrent training program entails combining strength training and endurance training as primary focuses.

As you may be aware, the idea that these two types of training interfere with one another has largely been debunked. I explain this here if you are interested.

However, there is a caveat to this.

In 2022, a systematic review & meta-analysis from Schumann et al. demonstrated convincingly that increases in strength and muscle size are largely unaffected by endurance training.

However, this paper did suggest that concurrent programs led to slightly less gains in vertical jump height; which is an indicator of power & speed more than it is strength.

Something to keep in mind is that only 1 out of the 43 analyzed studies actually had subjects perform power training.

The other 42 studies only had strength training as an intervention and used a vertical jump (measure of power) as one of the measured outcomes… meaning the subjects didn’t actually train for speed and power throughout the study.

Furthermore, this singular study had subjects perform the power training and endurance training in the same session; which was suggested to be less effective than performing them in separate sessions.

You could hypothesize that there’d have been greater improvement in the vertical jump improvements in the concurrent (strength + endurance) subjects if the programmed intervention was different, but you can’t say for sure.

Nonetheless, the overarching point is this: if left unattended, then improvements in speed and power may be less in a hybrid or concurrent program.

The easy fix is to spend some time training this; which should theoretically ward off this interference.

Even if all you care about is strength and muscle size, maintaining and improving your capacity for speed and power can- at times- make for easier progression in strength training.

So, no matter your overarching goals, it’s a justified necessity.

Anecdotally, this is a form of training I use often with clients.

When I have someone go from zero speed or power training to doing so regularly, they tend to note that they “feel” quicker, stronger, and bouncier.

It is also my experience that they make better progress with it than without it.

How to program speed and power training in a concurrent/hybrid program

There are two main points to keep in mind here:

Ideally, strength/power/speed training should be done in separate sessions than endurance training; separated by at least 3 hours

I understand this isn’t always possible on time-restricted schedules. However, if you can, you should.

If the power & speed work is being done in a workout that also has strength training, then the power & speed work should be done earlier in the session.

In the aforementioned paper suggesting the interference effect between strength and endurance training isn’t highly relevant, subjects found better results when the two forms of training were separated by at least 3 hours as opposed to being done in the same session.

This is the reason for the first bullet point.

Furthermore, in order to truly train power and speed, you need sufficient fuel in the tank to truly move at high velocites.

If you perform these later in the workout, it is likely you will become too fatigued to produce the velocites needed.

Plus, this form of exercise tends to be not very fatiguing, and you may even find yourself feeling more “primed” for your strength work after having done some power or speed exercises.

This is the reason for the second bullet point.

A framework that works best for most people is 1-2 power or speed based exercises for 1-2 working sets each at the start of your workout.

This doesn’t need to be done before every workout you do, but utilizing this in 1-2 of your workouts in the week can be very useful.

What specific exercises at what dose will vary greatly depending on the workout overall, goals of the program, and your training history.

The following are some examples to better characterize each category, power and speed:

Speed focused exercises:

Vertical jump, depth jump, box jump, etc.

Pogos, band assisted pogos, etc.

Kettlebell swings

10 yard sprint

Power focused exercises:

Power clean

Hang clean

Snatch

Push-press

Jerk

This list is not exhaustive, but it does include the exercises I most commonly utilize for these purposes in clients’ programs.

One thing to note is the magnitude of load being used in each category.

The loads overall are much lesser in the speed category than in the power category. As a result, you will be able to move at higher velocities than the “power” exercises.

Both categories of exercise, however, involve higher speeds than normal strength or hypertrophy training.

Now, let’s discuss what this might actually look like in a workout.

Assuming a person is doing full-body workouts, an example session could be the following (not including warm-up):

Band-assisted pogo jumps

Push-press

Barbell romanian deadlift

Flat dumbbell bench press

Machine leg extension

Cable crunches

If you were performing three full-body workouts in a week, then this could be the only session with this type of training or you could perform this type of session twice per week.

It’s hard for me to say what is best. What I would recommend is experimenting with different doses and seeing how you feel. People vary in what dose works best for them.

In any case, I hope that you find this information helpful.

If you have questions, or if you take action on this, then I encourage you to reach out by commenting below.